Testing Mail Messaging to Mobilize 2024-Only Voters in New Jersey

In the lead-up to New Jersey’s 2025 gubernatorial and legislative elections, the Center for Campaign Innovation conducted a messaging experiment designed to answer a narrow but important question. Could we mobilize voters who turned out in the 2024 general election but did not vote in the previous midterm, and if so, which messages were most effective at doing so?

This universe is particularly challenging. These voters are not disengaged, but their participation is inconsistent. They are reachable, yet often already saturated with voter contact. That combination makes them both valuable and difficult to move. Rather than testing whether mail as a tactic works, which is well established, this experiment focused on whether message framing meaningfully affects turnout among a key voting group.

Mail was chosen as the delivery vehicle because it allowed precise targeting and clean attribution back to individual voter records. In total, 27,327 voters were included in the experiment and randomly assigned into one of four groups. Three groups received mail, and one group was held out as a pure control that received no communication from us. Each treatment group received a series of three mail pieces in the weeks leading up to Election Day.

The first treatment used a standard “Get Out the Vote” reminder. The second focused on election integrity, emphasizing the steps taken to secure votes and reassuring voters that they could trust the process. The third took a behavioral approach, explicitly referencing the voter’s past participation and encouraging them to maintain their “streak” after having voted in 2024. Groups were balanced across key demographic and political variables to ensure that any observed differences could be attributed to the message rather than the composition of the universe.

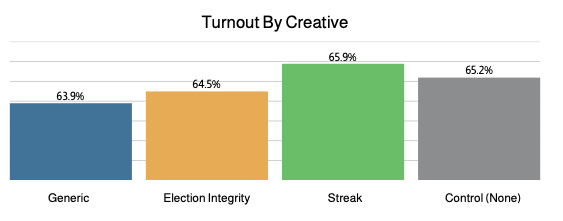

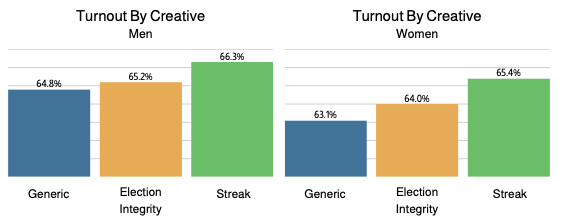

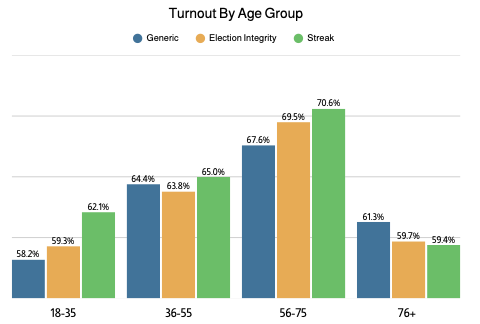

Turnout among the control group was 65.2 percent, reflecting both the high-propensity nature of the universe and the broader context of an election in which many campaigns and organizations were actively working to mobilize these same voters. Against that backdrop, the behavioral “streak” message produced the strongest result, with a turnout rate of 65.9 percent. That represents a 0.7-point lift over the control group. While modest in absolute terms, the streak message also outperformed the other two mail treatments by as much as two points, depending on the comparison.

By contrast, the generic GOTV message and the election integrity message both underperformed the streak-based mail and, in some cases, failed to outperform the control group at all. This pattern is important. It suggests that simply sending mail is not sufficient and that the content of the message meaningfully shapes its effectiveness.

From a statistical standpoint, these results do not meet conventional thresholds for significance. The high baseline turnout and crowded information environment made small effects harder to detect. But statistical significance is not the only lens for evaluation. The pattern was consistent across demographic subgroups, economically meaningful at scale, and actionable for future programs. Directional evidence from real-world experiments often matters more than statistically significant findings from unrealistic conditions.

The same pattern appears across most age cohorts. The primary exception is voters aged 76 and older, where more traditional, generic messaging performed best. That divergence reinforces the idea that different voters respond to different motivational cues and that no single message should be assumed to work universally.

One of the clearest lessons from this experiment emerges when the results are translated into cost terms. Because all treatment groups incurred identical production and postage costs, differences in turnout directly reflect differences in cost-effectiveness.

The program targeted 20,619 voters and generated 13,355 votes. If the streak message had replaced the other two treatments, those same 61,857 pieces would have generated 13,588 votes – 233 more votes at zero additional cost. Scaled to a program reaching 500,000 voters, that's 5,600 additional votes from better creative alone.

This isn't marginal optimization. In close races where campaigns routinely spend $50-100 per incremental vote through paid media or field operations, finding 5,600 votes in the creative testing budget is transformative.

This is where the broader implication of the experiment comes into focus. The primary takeaway is not simply that a behavioral message outperformed other mail copy, but that failing to test creative imposes real and measurable costs. When campaigns default to untested messages, they risk spending the same amount of money for fewer votes. In high-turnout environments, where margins are thin and persuasion is limited, that inefficiency matters.

As campaigns and allied organizations plan future voter contact programs, the evidence here argues strongly for fewer assumptions, more experimentation, and a greater willingness to invest in learning before scaling.

This experiment reinforces a simple but often overlooked point: the question is not whether to invest in turnout efforts, but whether those efforts are being optimized. Message choice is not cosmetic or secondary. It is a strategic decision that determines whether a program merely spends money or actually moves votes.

Campaigns that fail to test creative are not being cautious – they are gambling with scarce resources. In competitive elections, creative testing is not a luxury. It is the difference between winning and losing.